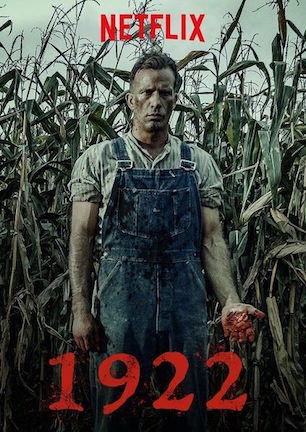

Studio: Netflix

Director: Zak Hilditch

Writer: Zak Hilditch

Producer: Ross M. Dinerstein

Stars: Thomas Jane, Molly Parker, Dylan Schmid, Kaitlyn Bernard, Bob Frazer, Brian d’Arcy James, Neal McDonough

Review Score:

Summary:

Enlisting his son to help murder his wife leads to unexpectedly haunting consequences for a downtrodden country farmer.

Review:

Where does “1922” rank on the list of Thomas Jane-starring Stephen King adaptations? Somewhere above “Dreamcatcher” certainly, but below “The Mist,” to be sure. Writer/director Zak Hilditch summons a solid sampling of Darabont-esque eeriness and human tragedy from the latter, though his film also finds its stride stymied by a thick rope of casual ambling that characterizes the former.

No middle ground exists between Wilfred James, a simple farmer with determined passion for a country lifestyle, and his wife Arlette, whose 100-acre inheritance of adjacent farmland could be the answer to the couple’s financial and marital woes. Arlette’s dream of moving to Omaha is hers alone however, and Wilfred doesn’t want to hear another word about city living.

When he becomes threatened by Arlette’s authoritative assurance that she is going to sell the property, file for divorce, and take their 14-year-old son Henry whether anyone likes it or not, Wilfred feels compelled to take action. Worming conspiratorial words into their son’s ear, Wilfred convinces Henry that Arlette has it out for the boy’s relationship with a neighboring farmer’s daughter. Henry soon swings to Wilfred’s side, with father and son daring to do a devious deed to protect their interests at the expense of Arlette’s life.

Having originally come from Stephen King’s words in the “Full Dark, No Stars” collection, the story of course only begins here. “1922” essentially operates much like a classic EC Comics morality tale, where selfishly committing an evil act topples a domino line of vengeful consequences at an almost comically alarming clip.

This particular parable dispenses with direct shambling corpse ghoulishness, preferring instead to dole out comeuppances in psychologically tormenting fashion. Wilfred’s ongoing guilt manifests as one singularly persistent ghost, who may or may not be in his mind, accompanied by an army of thematically emblematic rats, whose reality is evidenced by a proclivity for gnawing on the living and the dead alike.

In those regards, “1922” may have more in common with Edgar Allan Poe than with Bill Gaines. Yet it isn’t just the “Tales from the Crypt” influence earmarking Stephen King style all over the content. Trading fictional Maine suburbs for the rural cornrows of Hemingford Home in Nebraska, “1922” harkens back to the earthier roots of King’s earlier work, complemented by the closed door secrets, indulgence in sinister urges, and desperate descents into madness that earned his household name in the first place.

Thomas Jane sinks his teeth into Wilfred, and into each other, though getting into his performance requires getting behind a curiously cumbersome drawl. Jane pulls his country accent through a jaw wired shut around a baseball, forcing lines between stiff lips as if each word is a painful burden begging his mouth to move. It’s an odd acting choice that is undeniably distracting, yet it strangely starts fitting like a comfy old slipper by the film’s end through blunt force of its insistent consistency.

Thomas Jane’s commitment keeps Wilfred charged, even as a somewhat stereotypical villain whose eyes are permanently fixed in a brooding squint. Wilfred isn’t overcomplicated as a character, but Jane’s persona manages to eke out minor sympathy for him as an unpleasant protagonist deservedly doomed to never catch a fortunate break.

Supporting performers including Molly Parker, Dylan Schmid, and Neal McDonough aren’t afforded as many scenes as they need to bloom out of perfunctory functions. Still, their talents make the most out of the minutes they do share with Jane.

The indie production understandably swims as often as it can in Page Buckner’s impressive period production design, which seamlessly recreates the American Midwest in Vancouver. But the film’s skin does wrinkle from this excessive soaking. “1922’s” key flaw, while not a fatal one, is diminished effectiveness stemming from an overlong runtime.

Virtually no novella requires one hour and 41 minutes for a filmic retelling. Although not a demanding duration for any movie, the straightforward simplicity of “1922” doesn’t necessitate the space, nor does the film always fill it.

While a patient pace taxes the tank for more gas than the film carries, “1922” hit a higher rung than most, above average for sure, on the ladder of Stephen King adaptations. A moment involving a rat in a corpse’s mouth shines among memorable highlights on hand. It’s merely that the movie could cut with a deeper bite if its teeth were sharpened for more to-the-point precision.

Review Score: 65

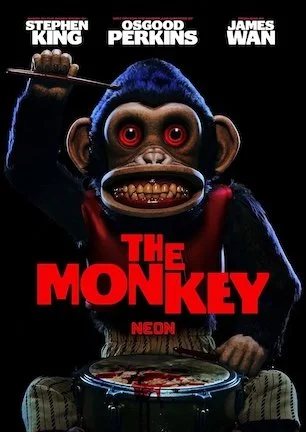

A charming chunk of cheddar that taps into the warm, fuzzy, and fugly feelings that make many of us nostalgic for the crude creature features of our youth.